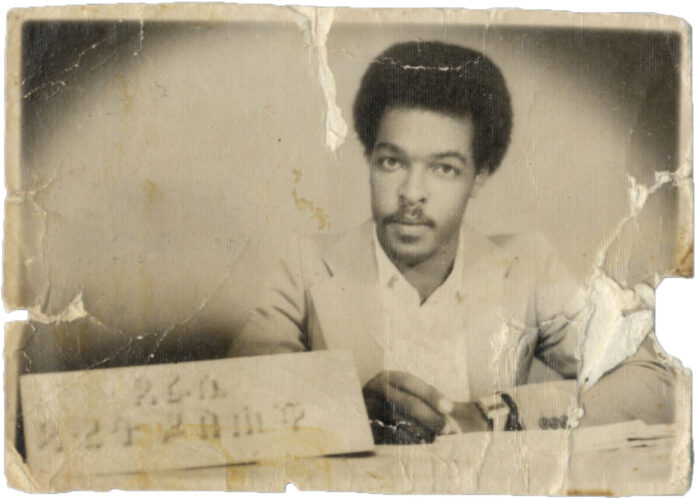

The world’s longest-imprisoned journalist remains virtually unknown and strangely invisible.

There are many reasons why the Swedish government has not managed to secure the release of Swedish-Eritrean journalist Dawit Isaak more than twenty years after his illegal imprisonment in Eritrea in 2001. The main responsibility for this failure obviously rests with the Eritrean dictator Isaias Afwerki and the country’s leadership who today count among the world’s most repressive regimes. They have proven themselves impervious to any and all appeals made on Mr. Isaak’s behalf.

Nevertheless, the Swedish side has not escaped its share of criticism.

Possibly the biggest failure to date is the fact that over the past two decades, Swedish authorities have not managed to make the fate of one of their own citizens into a true “cause célèbre.” By now, a broad awareness should exist of the horrendous crimes committed by the Eritrean regime against Mr. Isaak and thousands of his fellow Eritreans. Instead, the man who is one of the longest-imprisoned journalists in the world remains virtually unknown and strangely invisible, both at home and abroad.

THE INVISIBLE MAN

In Sweden, Dawit Isaak has remained essentially an outsider – an African immigrant, a Black man, living in a predominantly white society; a Swedish citizen but not a native Swede. Among the Swedish public, few are aware that the young refugee who took a job as a janitor in a Swedish church after fleeing his war-torn country in 1987 already in his early twenties had gained national prominence in Eritrea as a successful author and playwright. Several of his short stories were widely circulated and serialized on Eritrean Radio.

When Eritrea gained independence in 1993, Mr. Isaak returned. He became a journalist and a co-owner of Setit, Eritrea’s first independent newspaper. In September 2001, Isaak — who had obtained Swedish (and thereby EU) citizenship in 1992 — and more than a dozen other Eritrean journalists were swept up in President Afewerki’s crackdown on independent media and freedom of expression. Along with several prominent government officials (known as the G-15), the journalists had criticized Eritrea’s leadership for failing to implement the country’s constitution that was ratified in 1997 and to hold free and fair elections. The arrests occurred in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks in New York, so they went virtually unnoticed by the international community. Today, the Eritrean regime’s continuing brutal repression of civil society, especially journalists, is part of a global assault on civil liberties and media freedoms. Eritrea ranks consistently last, or nearly last on Reporters Without Borders’ annual World Press Freedom Index.

OFFICIAL SWEDISH FOOT-DRAGGING

In 2005, after a series of difficult negotiations between Swedish officials and the Eritrean leadership, Mr. Isaak — who has never been formally charged with a crime or presented in a court of law — briefly left prison, on a medical furlough. However, after only two days, and what turned out to be dangerously premature public comments by Swedish diplomats about Mr. Isaak’s rescue, he was re-arrested. Nothing has been heard from him since. Swedish officials apparently hoped that by keeping the case quiet and working behind the scenes, President Afewerki could be persuaded to order Dawit’s permanent release. Unfortunately, these hopes have proved futile; so has the wait for a possible regime change to solve the situation.

Unable to point to any obvious progress or success since then — and facing virtually no public pressure — Swedish officials have retreated behind a wall of silence, refusing to comment on even the most basic aspects of the case. The already limited coordination of efforts with international partners, especially in the European Union, appear to have stalled, overshadowed by more pressing matters like the war in Ukraine or the political protests in Iran.

This past October, the final report of an official, Parliament-ordered review of the official Swedish handling of Mr. Isaak’s case pointed to serious shortcomings, including the Swedish government’s failure to bring all suitable legal instruments to bear on the Eritrean government. To make matters worse, in direct defiance of the Parliament’s order, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to shield certain sensitive records in Mr. Isaak’s consular file from the internal review process.

Adding to the sense of official foot-dragging are the repeated refusals by the Swedish prosecution authorities to open a criminal investigation aimed at key members of the Eritrean leadership, under the principle of universal jurisdiction. The prosecutors cite the Eritrean government’s expected unwillingness to cooperate with such an investigation, and their wish not to jeopardize Mr. Isaak’s potential rescue. Meanwhile, Dawit Isaak remains imprisoned in inhumane conditions.

In a 2015 written ruling the Swedish Prosecutor General’s Office readily acknowledged that the crimes committed against Mr. Isaak rise to the level of “crimes against humanity.” Similar cases have been successfully prosecuted in Sweden, resulting, for example, in the July 2022 conviction of Iranian official Hamid Nouri, for the torture and execution of thousands of Iranian political prisoners in 1988.

A TROUBLING LACK OF URGENCY

What is completely lost in the current stalemate is any sense of urgency or determination to bring about Mr. Isaak’s release or a resolution of his case.

Through more than two decades Eritrea has incurred no serious costs for its brazen non-compliance with Swedish and international demands to free Dawit Isaak or to permit consular access to him. Swedish officials continue to cling to a strategy of silent diplomacy, showing no willingness or ability to shift course, even though the approach has yielded no tangible results.

In 2018, as part of an effort to reduce tensions with Eritrea, the UN Security Council voted to lift a range of sanctions (including several arms embargoes, travel bans, and asset freezes affecting specific Eritrean entities and officials). The UN had imposed the restrictions, beginning in 2009, in response to Eritrea’s aggressive military posture towards neighboring Djibouti and alleged arms deliveries to the terror organization Al-Shabaab in Somalia. The Swedish government actively supported the attempts at a rapprochement without obtaining even the slightest concessions from the Eritrean regime concerning the illegal imprisonment of Dawit Isaak and the overall human rights situation in the country.

For nearly eighteen years now Mr. Isaak’s family has received no information at all about his whereabouts or physical condition.

Some diplomats like the former US Chief of Mission in Asmara, Steve Walker are urging the international community to take a much more determined stance towards Eritrea. Last September, writing in The Atlantic magazine, Walker warned that any efforts to engage the Eritrean leadership must be “carefully calibrated” so as to avoid the appearance of indirectly legitimizing the criminality of the regime. Walker stressed that in light of the catastrophic human rights situation in Eritrea, “confrontation (not compromise) is both necessary and appropriate.” This should include a more direct countering of the Eritrean leadership’s disinformation and outright lies, along with strengthening the demands for humanitarian access to political prisoners and their immediate release. Walker further proposed the possible reinstatement of highly targeted economic and political sanctions, either through the United Nations or under the US Global Magnitsky Act (meaning the imposition of asset freezes and individual travel bans).

A year ago, a coalition of ten international human rights organizations, led by the Raoul Wallenberg Human Rights Centre (RWCHR) in Montreal, Canada – where I am a Senior Fellow – submitted a formal recommendation for sanctions against Eritrean officials under Canada’s Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act (Sergei Magnitsky Law) The coalition is currently exploring similar filings in other jurisdictions such as the US and the EU.

Official state actors in both the US and the EU have begun to take some limited steps in that direction, but these actions need to be expanded to more effectively address the deteriorating human rights situation in Eritrea.

In 2021, the EU imposed sanctions under its Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime, on General Abraha Kassa Nemariam, head of Eritrea’s powerful National Security Office which reports directly to President Afewerki. “The National Security Office is responsible for serious human rights violations in Eritrea, in particular arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances of persons and torture”, the EU statement reads. The US Treasury Department sanctioned General Kassa in November 2021.

There are also growing calls for an international tribunal to investigate the horrific crimes committed by Eritrean military forces in Tigray, in neighboring Ethiopia, including the rape and torture of civilians. Such a tribunal would mark a crucial step in the fight against impunity and, specifically, in the efforts to hold Eritrean leaders legally accountable for their crimes.

It is worth taking a moment to realize what was lost in 2001 — an exceptional group of writers and journalists eager to apply their considerable energy and talents to construct their home country, on democratic principles, after a long and brutal war of independence. In doing so, Dawit Isaak and his colleagues represent the very best, as Eritreans and as citizens of the world. It is time for the world to finally take notice and extend to them and to Eritrea’s long-suffering civilian population the support and justice they so urgently require.

Susanne Berger is the founder and coordinator of the Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative (RWI-70) and a senior fellow at the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights (RWCHR) in Montreal, Canada. She has been actively involved in the advocacy of the long-term disappeared, including the case of Swedish-Eritrean playwright and author Dawit Isaak.